I'm back with Holding___Space — a series of interviews with individuals who I believe are inspiring in the fields of mental health, wellness, and mindfulness. Through these interviews, I aim to bring a spotlight to the incredible work being done by these individuals and share their insights and experiences. I hope that by highlighting these people, I can guide both myself and you, the readers, on our own inner journeys and offer ourselves a source of inspiration as we work towards our own collective mental, emotional, and soul well-being.

In the second installment of this series, I have the privilege of presenting my interview with Ratu Nida Farihah. She is an Indonesian Product Manager living in Sydney, Australia. Meeting her, you're instantly drawn to her gentle, calming presence, her inquisitive yet kind eyes, and her warm smile. Beyond her professional role, Ratu stands strong as a domestic abuse survivor. Today, she is devoted to raising awareness about such abuse, bravely fostering discussions about trauma and the journey to recovery.

On a personal note, I've not often disclosed my own experience with partner violence, inflicted by an ex-boyfriend many years ago. The impacts of that relationship continue to shape aspects of my life. Through our shared experiences, we realised that one of the most potent tools in addressing this issue is to ensure women everywhere recognise the signs of abuse and empower them with the courage and strength to change their circumstances.

I hope through honest and open public conversations between two survivors like ourselves, we can shed light on these often-buried stories, offering both insight and hope to those facing (or have faced) similar challenges.

Without further ado, here's my conversation with Ratu.

CLARINTA: Ratu, how are you doing at the moment?

RATU: The question of "how are you" can be quite tricky, especially for those grappling with mental health. Often, we're torn between offering an honest reply or a polished one. With you, however, I feel a sense of trust. In this space you're holding, I can be genuine. So to answer: at this very moment, I'm feeling hopeful, calm, and eager to dive into this discussion with you.

CLARINTA: Can you share with me a bit about your upbringing, your family, and your cultural background? I think cultural context is important for the topic we're about to discuss.

RATU: I was raised in a conservative Muslim family. My father was from Banten, an area with a strong Muslim influence. Adding to that, my dad was born into an ulama family — which is a lineage of Islamic leaders. My father's family owns an Islamic school, and most of his siblings were sent to Saudi Arabia to learn about Islam, and returning back home to teach the theology. My father, however, was an outlier in his family by choosing a science major.

Despite his academic choices, he remained a strong practitioner of Islam, and I was brought up in this strict Islamic environment. As a young girl, I learned to read Arabic even before I became familiar with the alphabet. One of my earliest memories is of my father slapping my hand because I did not recite the Quran correctly. I remember running to my mom crying, and she simply told me to study harder. My mom was from Jakarta. She grew up in a religiously-moderate family, but she got married very young. It was an arranged marriage — they met only 3 times before that — and much of her personality was shaped by my father after tying the knot. Relatives would tell me she used to be different before the marriage.

CLARINTA: How do you feel the cultural context might have influenced or shaped your experiences, especially concerning the topic we're about to discuss?

RATU: Our upbringing, the values we get from our parents, and what society tells us — it shapes us more than we often realize. It forms the lens through which we view and engage with everything around us.

I'll give an example. In my late teens, just as I was beginning university, I was sexually assaulted by someone I knew. Considering how we rarely discuss sexuality in Indonesia due to cultural reasons, I didn’t have much knowledge about the topic of sex. I was fully covered from head to toe as usual, including a headscarf. But it still didn't keep me safe. That experience left me in a state of shock and disbelief, so much so that I couldn't even label it as 'rape' at the time. I experienced a pain I'd never known before. Not knowing what to do, coupled with my religious beliefs, made me feel as if I'd lost a part of myself, leading to a deep sense of worthlessness. I think this mindset played a part in my later experience with domestic violence, as from that moment I doubted if I will be worthy enough to deserve love.

I will not blame the religion because I know that at the core, I've always believed that every religion teaches love and kindness. However, people can sometimes lose sight of that.

CLARINTA: I'm truly sorry to hear about your experience. I completely resonate with what you said about religion – every religious and spiritual teaching essentially teaches us to be kind and good. I grew up with a different religion, but just like you, I barely knew anything about sex growing up. It was a taboo topic; a sinful act. As a result, I also felt my 'worthiness' as a human being was simply reduced to my sexual purity or impurity.

RATU: You know, a mentor once told me that humans possess a unique superpower: the ability to take away another person's power. We often do this through tactics like shaming and guilt-tripping. Such actions make individuals feel small over things that are inherently human. At the same time, our inherent desire as humans is to belong. Many of us strive to fit into what's expected of us by our families and communities. Especially for a child — like any plant — we will twist and distort ourselves into uncomfortable positions just to gain light and survive.

CLARINTA: Earlier, you eluded to the existence of some abuse in your upbringing. Were your parents physically violent too?

RATU: Sure. In many parts of Asia, it's almost seen as normal for parents to beat their kids, isn't it? Especially when they're not in control of their emotions, or emotionally dysregulated. We just accepted it as part of life.

CLARINTA: Yes, unfortunately I know exactly what you mean.

RATU: The sad part is, the way they treated us gets ingrained in us. We start seeing it as a reflection of our worth.

CLARINTA: Yes, as children, we couldn’t comprehend that it was our parents struggling with their emotions. Instead, we internalized it, thinking we must be the problem, and that we deserve such treatment.

RATU: Exactly. It's a vicious cycle.

Entering The Relationship

CLARINTA: How did you meet your former partner, and what drew you to him initially?

RATU: My sister's best friend introduced us. In our conservative family, dating wasn't casual; if you were seeing someone, marriage was always the end goal. Just like my mom, I only had a few meetings with him. Our families got acquainted, and before we knew it, we'd set a wedding date. What attracted me was his intellect. I've always been a bit of a bookworm, so our deep conversations really resonated with me. And he was very affectionate. At one point, during a lockdown, he even flew to Dubai, where I was working as a marketing manager, just to see me. I thought, "This person must genuinely love me." And my mother loved him. On paper, he ticked all the boxes: an Ivy League education, a top-tier job in a Big 4 consulting firm in Australia, and importantly for my family, he was Muslim. And also, given my dad's recent death at the time and his hope of seeing me married with someone of the same religion, I felt he'd have approved.

CLARINTA: Were there early signs of red flags in the relationship?

RATU: In hindsight, yes. Many. But I overlooked them, not trusting my gut. The most glaring incident was about two weeks before our wedding. I was at my office in Dubai, deep in a work chat with a male colleague. Out of nowhere, he storms in, furious about missed calls. My phone was always on silent during work, so of course I had missed them. His anger and the accusations, right there in front of my colleague, were shocking. He even snatched my phone, trying to "prove" I was cheating. Even though I knew his claims were untrue, I couldn't help but question myself and was frightened by his rage. I later called my mom, telling her I was considering postponing or even cancelling our wedding. But my mom blamed me, saying 'This is your fault. If you're about to get married, you shouldn't be talking to other men.'

CLARINTA: Oh no. That's heartbreaking.

RATU: It's crazy, isn't it? Though, I can't blame my mom; she did what she thought was right. But here I was, an MBA scholarship recipient, yet I couldn't see the situation for what it was. Instead, I blamed myself for causing his jealousy and even told him I'd distance myself from other men. He said he reacted that way because he loved me, and I just... believed him. The next day, I even quit my job because he asked me to. Everything happened in a blur.

CLARINTA: How did your family and friends perceive your relationship with him at this time?

RATU: My family, particularly my mom, was pleased with him. In their eyes, I was already behind schedule at 30 for getting married. But my friends were pretty shocked. They couldn't grasp the idea of marrying someone after just a few meetings. And that's the thing — when you listen to stories from survivors, it's crucial to recognize that their choices are often shaped by their cultural backdrop, traditions, religious beliefs, and their place in society. Sadly, not all of us have the luxury of absolute freedom, and for some, their cultural norms can feel like a cage that's difficult to escape from.

Experiencing Abuse

CLARINTA: How and when did the abusive behaviour begin?

RATU: It began even before the wedding, but there's this concept in domestic violence called the "cycle of abuse." The pattern is, as the abuse intensifies over time, there are also moments of love-bombing and apologies. It was like an emotional roller coaster. I felt like I was constantly walking on eggshells, never knowing how my day would unfold. Some days he'd treat me like I was a queen, and the next, I'd be trembling under my blanket, praying he wouldn't come at me with a knife during one of his violent outbursts. He'd often tell me he'd kill me, and he knew I had nowhere else to turn. Even my own mother would send me back to him.

If we were out and other men glanced at me, his jealousy would spiral. Once home, he'd accuse me of seeking attention. He'd inspect my phone and force me to block contacts on a whim. Small issues would blow up into huge issues. Shouting and yelling was the norm. I often had nightmares of him trying to kill me. He'd wake me up, saying I'd been shouting fearfully in my sleep. I could never confess those nightmares were about him; I was afraid it'd only make him more angry.

The whole situation became even more suffocating when Australia went into full lockdown due to Covid. We were both working from home, and it was like living out a horror film, trapped and terrorized in my own space.

CLARINTA: Wow, hearing you talk about the cycle of abuse, it really resonates. As I mentioned before this conversation, I went through something similar when I was much younger and spent time in therapy unpacking it. My relationship at that time lasted about a year and a half.

For myself, being young, I didn't even realize that what I was experiencing was 'abuse'. I thought, "He's my boyfriend, he can't be abusive." And just like your experience, after he hurt me, he'd apologize like he meant it. He was perpetually angry, and constantly putting me down verbally. I also endured over a year of almost daily physical violence. It was also over minor things - if I talked to other guys, being slightly late to meet him, not replying to his messages quickly enough, or standing up for myself. Being so naive, I couldn't even recognize that what I was enduring was 'abuse'. But then he'd have these moments where he'd genuinely seem remorseful and apologize. Every time I thought, "Maybe he truly regrets it this time," and I'd forgive him. He'd be extra sweet and caring after, earning my trust again. That's when the self-blame kicked in. I'd think, "Maybe it was my fault. Maybe I deserved it." Now, as an adult, it feels so twisted. When someone asks, "Why didn't you just leave?" I wish they knew it's never that straightforward. There's always that hope they might change. And mixed in is the feeling that maybe you don’t really deserve any better.

RATU: Our stories seem to echo each other in many ways. When I started learning about domestic or partner violence, I came across the term DARVO. That acronym stands for Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. Based on what you're sharing, I'm guessing you might've encountered this too. When confronted, abusers often play the victim card and twist things around to paint us as the villains.

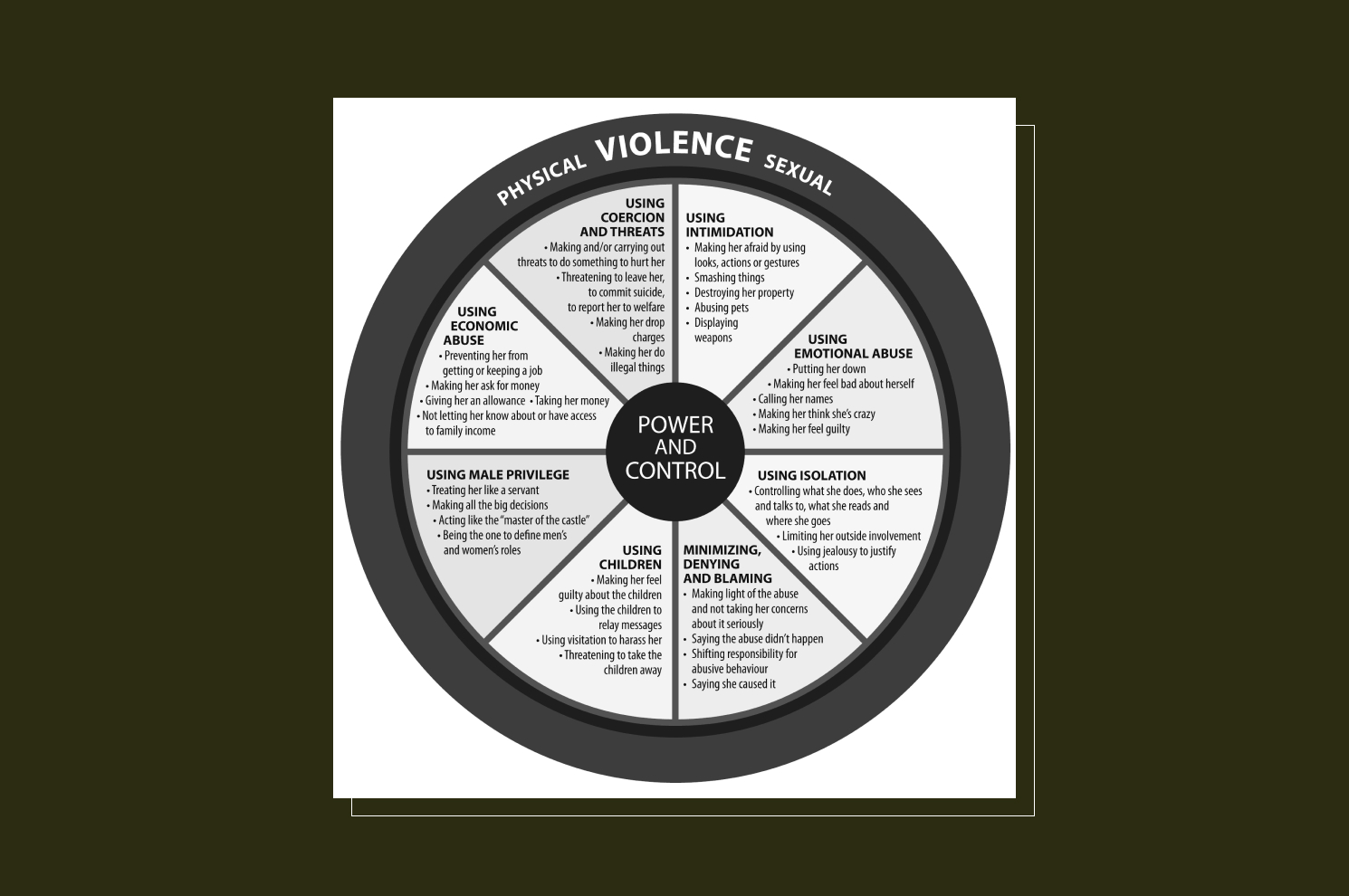

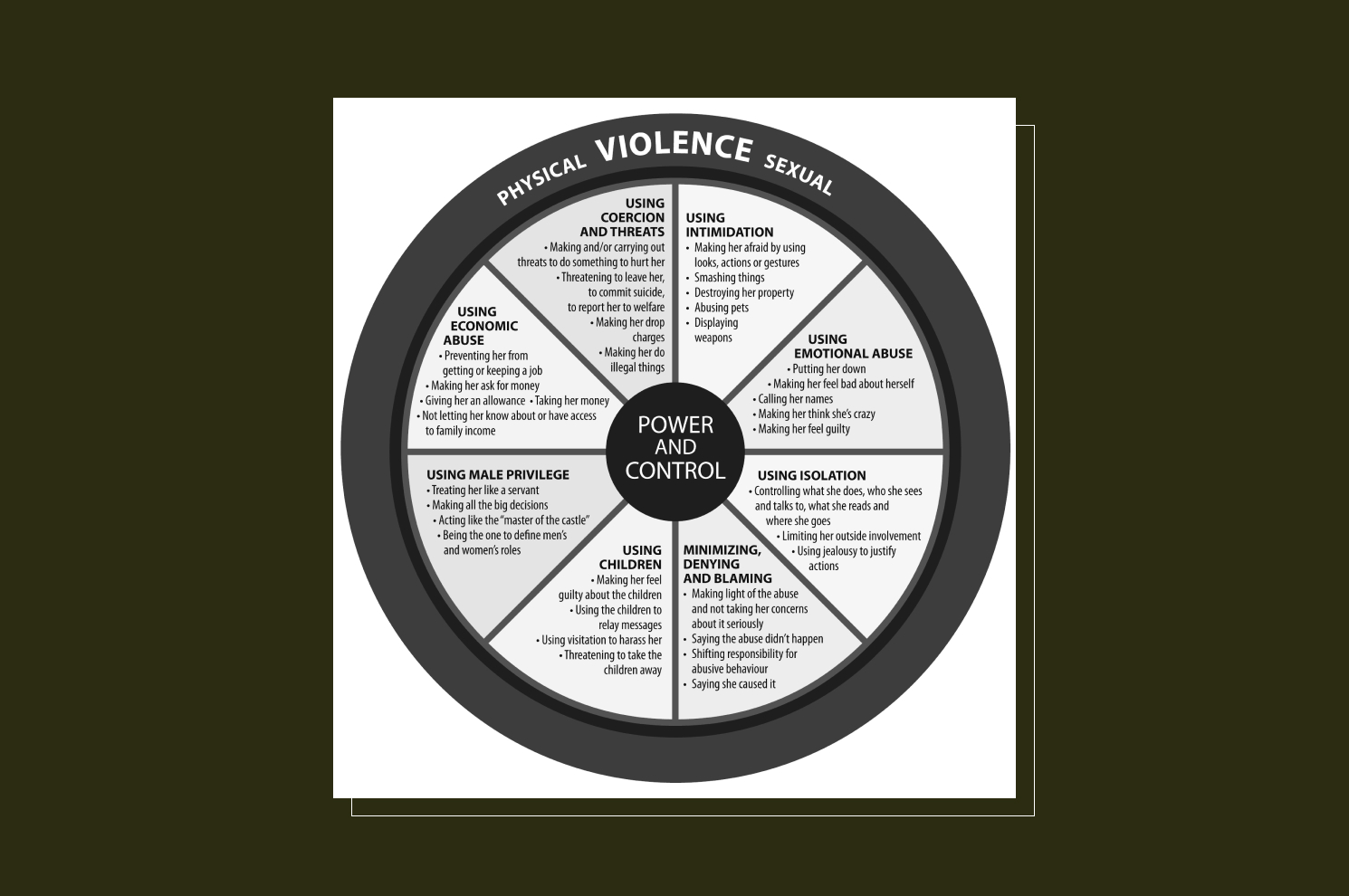

I think growing up in a home filled with violence also made me see my experiences as just regular marital conflict. But in reality, it was all about dominance and manipulation. And it wasn't just the physical – there was emotional and financial abuse as well. There's this concept called the 'circle of power and control' (see below). It encompasses emotional, physical, sexual, and economic abuse. In abusive relationships, it's rare for it to remain just one kind of abuse. The longer it's tolerated, the more it branches out.

CLARINTA: How did the abuse affect your mental health, self-worth, and daily life?

RATU: It really wore me down. Even though I kept hoping things would get better, it felt like the abuse was chipping away at my sanity. I changed so much, always tiptoeing around him, trying not to make him angry. Even at work, I was nervous about interacting with male colleagues. I'd quickly delete any messages from male friends, and he pushed me to block my friends on social media. If any man so much as glanced my way, he'd accuse me of flirting. So I just stopped bothering about my appearance, and dressed down to avoid his outbursts. My confidence took a nosedive, and I felt like I was losing my sense of self.

Honestly, I felt trapped and broken. Every day was filled with fear and isolation. At my lowest, I believed there were only two ways out — if he killed me, or if I killed myself.

CLARINTA: Were there cultural or societal pressures that made it more challenging to speak out or seek help?

RATU: Yes, of course. The cultural aspect that we discussed before closed me off from understanding what rights I actually deserved. In Indonesian culture, unfortunately we normalised violence within a family and within a marriage.

CLARINTA: It's sad but true. In our culture, some are so used to this behavior that they might even ask, "What did you do to provoke him?" Which is a damaging and victim-blaming mentality.

RATU: You know, I couldn't even see that I was being abused. My best friend pointed it out once, and I instantly defended him, saying, "No, he just really loves me." Her response stuck with me: "That sounds exactly like what a victim would say." It took some time, but being in Australia, where there’s strong recognition of domestic abuse, really opened my eyes. I came to understand that nobody should ever be treated like that.

The Turning Point & The Aftermath

CLARINTA: What was the turning point that made you decide to leave the relationship?

RATU: One day, his rage erupted again. After he threatened to kill me, I became so terrified that I ran out of the house. Ironically, it was a work day, and I had an important meeting. I grabbed my laptop and, finding a public library with WiFi, I logged into my work call. I'd been crying so much that my eyes were completely puffy. I recall being on that video call with my manager, tears still in my eyes, telling her I might need to resign to save my marriage. But here's the thing: my manager, being Australian and having a background in social work, could immediately sense something was wrong. She probed, asking me question after question. I answered her honestly. And by the end, she said, "I believe you're a victim of domestic violence. Please don’t go back home. Here's the number for the domestic abuse hotline."

That night, I reached out to a friend and stayed on her sofa. I also rang the Domestic Abuse hotline. The voice on the other end asked me many questions, most of which I answered yes to. And then they told me, "You are a victim of domestic violence. Please don't return home. We'll assist with a shelter and contact the police for you."

CLARINTA: That's incredible. I'm so glad your manager sensed something wasn't right and asked you those questions.

RATU: It's important for people to know - for survivors, sometimes it's not about the words they say. Traumatized people often withhold the truth, because we are living in fear, unsure of who to trust. My manager and my best friend in this case, saved my life.

CLARINTA: Can you describe the process of seeking help and eventually moving to a domestic abuse shelter? How was your experience living in the shelter?

RATU: It was a rollercoaster. I was moved between multiple crisis shelters. These places are designed for survivor protection, so our connection to the outside world was minimal. You know the Netflix series, 'Maid'? It was eerily similar – no internet to prevent abusers from tracking us down. The shelter was modest, with a few rooms, and I had a bed in one of them. The cold was what I remember. The winter chill seeped through everything - the air, the water, even the walls of the shelter.

CLARINTA: I find it really interesting you mention about the cold, because I thought you would mention how you were finally safe from your ex-husband.

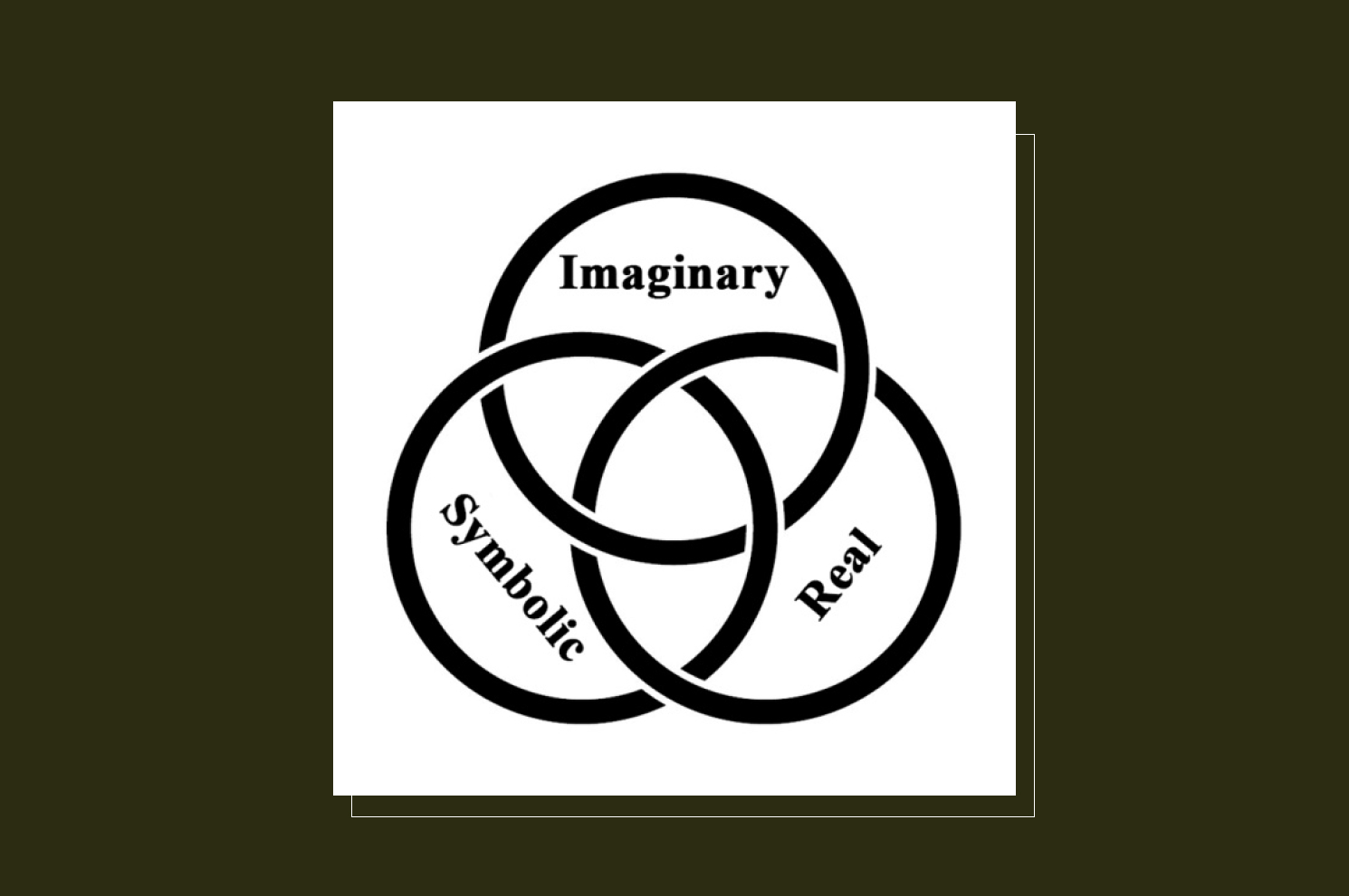

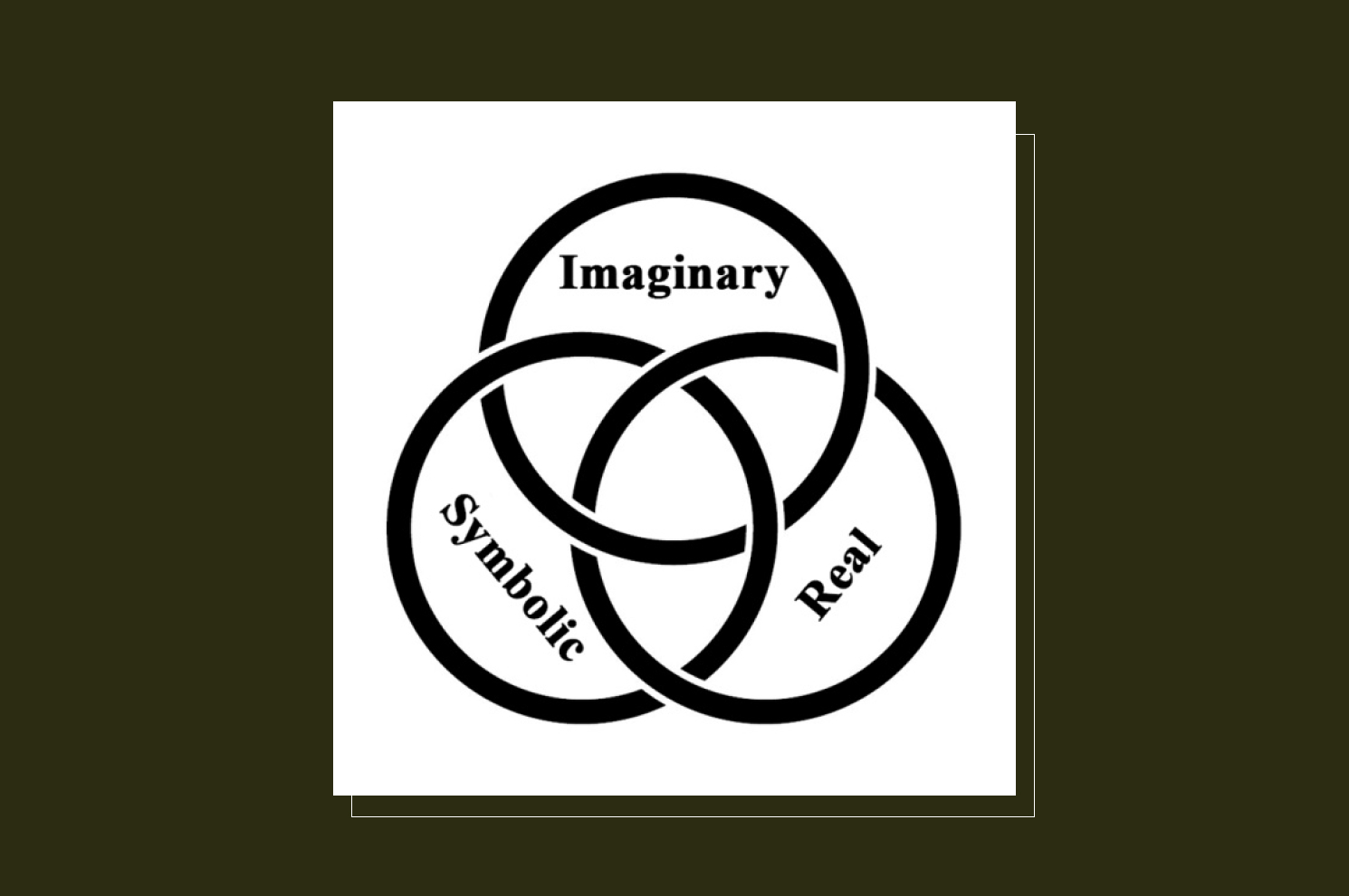

RATU: It’s interesting you mention that. Have you come across Lacan’s Borromean Knot theory? It explains how we perceive and understand our own realities. Basically, it's structured into three areas: Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real. The Imaginary is our immediate lived experience — how the world presents itself to us. The Symbolic captures the societal rules and norms we've followed all our lives, shaping our perceptions. The Real, often overlooked because we're engrossed in the first two, is those indescribable experiences — like traumas — that completely shake up our understanding of the world.

In other words, we humans think more in terms of symbols rather than the actual reality. Like, when you think of a home, you picture warmth, comfort, safety, right? Even during the times I was abused, I'd take a bath at home and let hot water run over me just to numb the pain, to make myself believe that I was safe even though I wasn’t.

Now, the shelter was a safe place. I was away from my abuser. But in my mind, the idea of a shelter was more about escaping, not about warmth. Even though I was safe, the shelter was cold and I felt incredibly lonely. I was surrounded by other survivors, each one grappling with their own trauma. I vividly remember my first time in the shared kitchen. I met a woman with half of her face brutally swollen and bruised. Even though I'm obviously a non-threatening person, she looked so terrified and instinctively flinched as I approached. It was really jarring to realise that another victim was so traumatised that even my presence made her recoil.

At that time, I also struggled with my mental health. After what happened, I was diagnosed with CPTSD - I had constant flashbacks & nightmares. At the same time, I had to go back and forth to the police & the court, to deal with legal paperwork to keep my immigration status — my ex-husband was Australian — and juggling my work at the same time. At the shelter, my social worker educated me about my rights and options. They also assisted me in going to the police to file an AVO, which is a restraining order against my husband. They also helped me in getting basic needs like clothes and food, because when I fled home, I didn't bring any of my things.

CLARINTA: Did your mom know you had moved to a shelter at this point?

RATU: That's where generational trauma truly takes its toll. When I called and told her about the situation, she felt I should either return to him and resolve our issues or find another man to marry. In our culture, being a widow—or even a victim of abuse—is a shame. In her eyes, I had brought dishonour and shame to our family. Instead of trying to hear my story, she cut ties with me for two years. She blocked me everywhere—on social media, WhatsApp, everywhere.

CLARINTA: That's terrible, I'm so sorry to hear that.

RATU: It's hard to blame her entirely. I believe she endured similar treatment herself. She simply didn't know better. And unlike me, she didn't have as many options or the education to find alternatives for herself. Maybe she thought, "If I endured this, you should too."

I've come to accept that she couldn't be the protective mother I needed. And fortunately, I've found a chosen family here—my manager, my best friend. They're my family now.

CLARINTA: After leaving the shelter, how did the relocation to an independent apartment come about? How has living independently in your own space been?

RATU: I think the challenges of managing work while at the shelter motivated me to quickly seek a stable place. I really felt how crucial it was to be financially stable and independent. Work was my only lifeline at that point, something I needed to cling to if I hoped to rebuild my life. I had only $30 in my bank account then and couldn't touch our joint savings.

The move itself was an emotional whirlwind — feelings of grief, abandonment, longing, and fear mixed with gratitude for another shot at life and a new sense of freedom. Living in my own space has been so important in my recovery process. It's a place where I can feel safe, and take the time to heal.

Therapy, Healing and Self Rediscovery

CLARINTA: What kind of after-effects & challenges do you still have to deal with on a day to day basis as a result of the abusive relationship?

RATU: The after-effects of domestic violence is so deep and pervasive. If I had to categorize them, I'd say there are external and internal challenges. On the outside, it's impacted every facet of my life - my family relationship, friendships, social network, living situation, financial standing, and professional life. My own mother, as I mentioned before, turned against me. Several friendships dissolved too. It's not necessarily their failing; many simply aren't equipped to understand or help me in the aftermath. The weight of discussing domestic violence created an awkward tension for many of them. While it's painful to see my circle diminish, it also affirmed who my core support circle of people are.

Financial stability, a challenge many other survivors struggle with, also became a main concern for me. I consider myself fortunate to have regained stability through my job, but many women, particularly those with children or student debts, aren't so lucky. That's why it's my firm belief that every woman needs to have a job, however small or modest. It's not just about money, but the autonomy and security it offers, which prevents us from being trapped in abusive relationships. Financial abuse is also an often-overlooked component of domestic abuse, which undermines our autonomy and self-worth.

At my lowest point, I was declining casual simple treats I used to be able to afford without thinking, like ice creams or an after-work drink with colleagues. Still, I’m grateful for the financial support I also received from the Australian government. It’s important for taxpayers to know how their contributions uplift survivors.

CLARINTA: What about the internal struggles you mentioned?

RATU: I've mentioned this earlier, but I was diagnosed with PTSD. The effects have been relentless. I'm haunted by nightmares every night, waking up at 1 AM as if on schedule. I tried using the Calm app to ease myself back to sleep, and while it helps at times, there are instances when sleep eludes me completely. After tossing and turning for a few hours, I usually resign to it and start my sunrise walks. It's a bit ironic—people like Elon Musk advocate early morning walks as a productivity booster, but for me, it's my nightmares that drive this ritual.

There are also many triggers, spread everywhere like landmines. Just recently, an internet technician's visit to my apartment spiraled into a nightmare where my ex violently confronts me about allowing another man inside our home. Or the panic attacks I have whenever my train stops at the station near our former shared home. Some workplace interactions, especially with male colleagues, have become anxiety-inducing. The unpredictability of PTSD triggers means I am stripped of my sense of normalcy.

CLARINTA: After your experience, how important was it for you to seek professional therapy or counseling? How did these sessions impact your recovery?

RATU: At first, I didn’t even realize therapy was something I needed. My initial aim was simple: to be fully functioning at work. Oddly enough, the motivation to seek therapy wasn’t really for myself, but to perform well at my job. Maybe that’s my people-pleaser side showing up again. So, with that focus on work, I found government-offered therapy sessions for survivors. That's when my healing journey started and, in many ways, my awakening.

That first session was a revelation. Pouring out my life's story to the therapist, it was as if a hundred light switches turned on. It explained why I felt perpetually damaged, why love seemed out of reach, and why there was this persistent feeling of emptiness. Turns out, much of that stemmed from what I endured growing up. The childhood abuse, constantly witnessing violence, the sexual assault, the years of feeling trapped, and then the domestic abuse in my marriage – all were rooted in this profound sense of unworthiness.

I spent most of the first month's sessions in tears. I connected with not only my pain but also the pain of countless women, including those of my ancestors, who suffered in silence. It was very humbling in an unexpected way.

CLARINTA: I complete understand how this feels. Therapy for me also unlocked the realisation that my entire life was a series of connected events, leading me to my present state of being. It was an equally humbling experience for me, and led me to feel compassion for both my past self and for others in my life. For me, I’ve since gone through EMDR, schema & exposure in the last 2 years. Also, understanding that traumatic experiences changes our brain structure has helped me massively in accepting that although my mind might have moved on, my nervous system has not. Were there specific types of therapies or approaches that you found particularly helpful?

RATU: I've done various forms of therapy like CBT, somatic therapy, grounding techniques, and I've integrated practices like meditation and yoga into my recovery process. Being part of a support group with fellow domestic violence survivors has also been cathartic. But the fundamental part of my healing journey has been rebuilding my self-worth. It's devastating to realize that many survivors, including myself, internalize the wrongs that was done to us. We need to stop feeling ashamed for the abuse we endured. Therapists help dismantle this belief, placing responsibility where it truly lies. This is critical for healing. It allows survivors to move forward, not just for their own sake, but to uplift others who've experienced similar traumas. Your conversation with me now, holding this space—it's part of that healing cycle, and I try to provide the same for others.

I would say at the end of the day, though, healing and recovery is about consistency and to keep practicing it. No matter the therapy methods or books we read, it comes back to our commitment to work on ourselves and embody it in our daily lives. When we are faithful to a practice or ritual, it will be faithful back to us.

CLARINTA: That's so eloquently put. I've also started attending a group therapy session weekly over the past five months. The group is diverse — some healing from past sexual assault, another dealing with the trauma of a suicidal parent, and many confronting the scars of childhood emotional neglect. While the group sessions can be intensely heavy, those 90 minutes where we sit with another’s pain, have become the most moving and most impactful part of my week. What else have you found helped you?

RATU: Maintaining a healthy support circle is essential for a survivor. During those heightened moments of vulnerability, even the smallest things can set off distressing triggers. I also strongly believe in the value of ongoing therapy. Sometimes, just when we think we've made progress and are ‘healed’, life throws us a curveball and presents a new challenge or trigger. I've often wondered if there's a scientific explanation behind this. Haven't you felt that way too? We overcome one hurdle, feel empowered, only to be taken aback by something even more overwhelming.

So it’s essential to have professionals - whether a therapist, coach, or social worker - and a supportive community by our side. It's unrealistic to expect our loved ones to shoulder everything, particularly if they were, unfortunately, a source of our trauma. We must take the initiative to find our "tribe", those who constantly remind us to treat ourselves with kindness and love. Personally, I've also found healing in art. Whether it's through poetry, painting, music, photography, or theatrical performances, art has become an outlet for me. It reminds me that we are all humans with our struggles, just trying to make it through another day.

CLARINTA: What would you like to say to others who might be in a similar situation or those who suspect someone they know might be facing domestic abuse?

RATU: I'd start by saying I am truly sorry that this has happened to you. Please know that I see you, believe you, and feel your pain. This isn't your fault, even if it sometimes feels that way. Abuse and violence were choices the perpetrator made, and it's a tragedy when such actions come from someone you deeply love and trust. But remember, you don't have to endure it. Your mental and physical well-being should always be your primary concern. Understand that you're deserving of love, respect, and security, just like everyone else. Reaching out for help is not a sign of defeat; it's a testament to your resilience and refusal to give up living. Standing up for yourself and breaking free from this cycle, particularly if it's rooted in generational trauma, may mean losing family members and stepping out of your comfort zone. Many who you believed had your back might misunderstand or judge you, but remember, those resistant to your growth were never in it for love; it was about power and control. Let them go.

This might be a metamorphic phase for you, but it's also a journey towards rediscovering yourself. You'll come to know who you truly are, beyond labels and societal expectations. You'll surround yourself with those who genuinely care, seeing and cherishing you for the person you are. Trust me, many empathetic souls are out there, waiting to support you. And while the path to recovery might be challenging, it promises to be one of the most transformative experiences of your life.

CLARINTA: Beautifully said, I experienced this transformative phase myself as well. In your opinion, how can communities and individuals better support survivors of domestic or partner violence?

RATU: The key is education and awareness. Recognize that domestic/partner violence follows a familiar pattern, and is preventable if you notice the signs. Listen actively to the stories of survivors and understand their insights. When survivors decide to share their truths, receive them with compassion and understanding. Their stories have the potential to save future generations, and to provide immediate support to those currently suffering in silence.

CLARINTA: Building on that, I think it's also about challenging and reshaping deeply ingrained narratives. For so long, many of us have been conditioned to believe that we should prioritize sacrifice and endure suffering — mentally, physically — because it's culturally expected. And it's not just partners; even children are often taught to accept violence from parents under the guise of discipline or 'tough love.' But when someone, with the same socioeconomic and cultural background, steps up and declares, "No, your well-being also matters, just as much. You deserve better", it disrupts that old narrative. Presenting this alternative viewpoint at least offers the chance for that person to reconsider deeply held societal conditioning and provides them an opportunity to think differently.

RATU: Exactly. Representation matters. Unless we witness others breaking free from abusive relationships, and standing on their own two feet again, it can be hard to imagine that path for ourselves. I remember connecting with you because you openly talked about your journey with CPTSD. Your explorations into meditation deeply resonated with me and even influenced some steps in my own healing process. I think sharing, in its purest and most authentic form, is transformative. By being open about our experiences, we not only support our own growth but potentially light the way for others.

Future Aspirations

CLARINTA: Now that you're building a new chapter in your life, what are your hopes and aspirations for the future?

RATU: My vision is for a world that is just and equal, where we all, men and women, come together in mutual respect to contribute to the greater good of humanity. After all, we are called 'homo sapiens' for a reason – we're meant to be wise beings. We might never fully achieve this vision, but by recognizing that men and women are fundamentally equal as human beings, we can change the dynamics of our relationships and interactions.

Also, I want to witness a world where women stand empowered. The current struggles and generational trauma many of us face trace back to age-old systems of patriarchy. We need to actively question and reframe our traditional gender roles. Women have a reservoir of resilience and strength that is often overlooked. To truly progress, we must shift from a mindset of competition and judgment to one of collective empowerment. Every triumph for one woman should be celebrated as a collective victory.

CLARINTA: As we wrap up our conversation, do you have any parting words or insights you'd like to share with the reader?

RATU: I would like to quote an author I deeply admire, Yung Pueblo: “Our greatest asset in transforming the world and uplifting human dignity is healing ourselves so deeply that we become unwilling to harm others directly or indirectly.” This, to me, encapsulates our conversation today.

CLARINTA: Thank you for letting me hold space for your story.

___

Resources

Below are important Domestic/Partner Violence resources from Ratu:

AUSTRALIA:

In Australia, the resources are more comprehensive, and there's a significant effort to ensure those affected by domestic violence get the support they need:

- Emergency Assistance: Dial 000 for Police and Ambulance if in immediate danger.

- Counseling and Support: 1800RESPECT - A 24/7 national counselling and support service for those impacted by domestic, family, or sexual violence. Chat online.

- Trauma Counseling: Full Stop - Offers trauma counselling & recovery services for individuals facing or having faced DV. Call 1800 385 578.

- Legal Service: Women’s Legal Services - Free, confidential legal advice centered on family law, DV, and sexual assault. Reach them at: 1800 801 501.

- Community Support: Women & Girls Emergency Center (@WAGEC) - Provides crisis support, mentoring, and more, including training, campaigns, and advocacy efforts. Ratu is also currently a mentor here.

INDONESIA:

For Indonesia, unfortunately, the support and awareness is still minimal. However, here are some numbers & organisation you can reach out to:

- Domestic Violence Reporting: SAPA - To report DV: Call 129 or WhatsApp 08111129129.

- Legal Assistance: LBH Apik WhatsApp – Reachable at 0813 8882 2669 (9:00-21:00 WIB).

- Hotlines: P2TP2A DKI Jakarta Hotline – Dial 112. Pelayanan Sosial Anak (TePSA) – Call 1 500 771.

- Women's Commission: Komnas Perempuan - For assistance, dial 021 390 3922 or email at petugaspengaduan@komnasperempuan.go.id.

- Psychological Counselling: Indonesian Psychological Healthcare Center (IndoPsyCare). You can also read a previous interview with a clinical psychologist on my journal here.

You can also reach out to us with your own stories through our social media at @clarinta & @ratunida.

___

Further Reading & Research:

- People who were abused as children are more likely to be abused as an adult (UK Office for National Statistics, 2021)

- Intimate partner violence and traumatic brain injury: An invisible public health epidemic (Harvard Medical School, 2022)

- Risk and Protective Factors for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Perpetration (CDC.gov, 2020)

- Psychotherapy leads in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (Harvard Medical School, 2019)

- ‘One Foot in the Present, One Foot in the Past:’ Understanding E.M.D.R. (The New York Times, 2022)

I'm back with Holding___Space — a series of interviews with individuals who I believe are inspiring in the fields of mental health, wellness, and mindfulness. Through these interviews, I aim to bring a spotlight to the incredible work being done by these individuals and share their insights and experiences. I hope that by highlighting these people, I can guide both myself and you, the readers, on our own inner journeys and offer ourselves a source of inspiration as we work towards our own collective mental, emotional, and soul well-being.

In the second installment of this series, I have the privilege of presenting my interview with Ratu Nida Farihah. She is an Indonesian Product Manager living in Sydney, Australia. Meeting her, you're instantly drawn to her gentle, calming presence, her inquisitive yet kind eyes, and her warm smile. Beyond her professional role, Ratu stands strong as a domestic abuse survivor. Today, she is devoted to raising awareness about such abuse, bravely fostering discussions about trauma and the journey to recovery.

On a personal note, I've not often disclosed my own experience with partner violence, inflicted by an ex-boyfriend many years ago. The impacts of that relationship continue to shape aspects of my life. Through our shared experiences, we realised that one of the most potent tools in addressing this issue is to ensure women everywhere recognise the signs of abuse and empower them with the courage and strength to change their circumstances.

I hope through honest and open public conversations between two survivors like ourselves, we can shed light on these often-buried stories, offering both insight and hope to those facing (or have faced) similar challenges.

Without further ado, here's my conversation with Ratu.

CLARINTA: Ratu, how are you doing at the moment?

RATU: The question of "how are you" can be quite tricky, especially for those grappling with mental health. Often, we're torn between offering an honest reply or a polished one. With you, however, I feel a sense of trust. In this space you're holding, I can be genuine. So to answer: at this very moment, I'm feeling hopeful, calm, and eager to dive into this discussion with you.

CLARINTA: Can you share with me a bit about your upbringing, your family, and your cultural background? I think cultural context is important for the topic we're about to discuss.

RATU: I was raised in a conservative Muslim family. My father was from Banten, an area with a strong Muslim influence. Adding to that, my dad was born into an ulama family — which is a lineage of Islamic leaders. My father's family owns an Islamic school, and most of his siblings were sent to Saudi Arabia to learn about Islam, and returning back home to teach the theology. My father, however, was an outlier in his family by choosing a science major.

Despite his academic choices, he remained a strong practitioner of Islam, and I was brought up in this strict Islamic environment. As a young girl, I learned to read Arabic even before I became familiar with the alphabet. One of my earliest memories is of my father slapping my hand because I did not recite the Quran correctly. I remember running to my mom crying, and she simply told me to study harder. My mom was from Jakarta. She grew up in a religiously-moderate family, but she got married very young. It was an arranged marriage — they met only 3 times before that — and much of her personality was shaped by my father after tying the knot. Relatives would tell me she used to be different before the marriage.

CLARINTA: How do you feel the cultural context might have influenced or shaped your experiences, especially concerning the topic we're about to discuss?

RATU: Our upbringing, the values we get from our parents, and what society tells us — it shapes us more than we often realize. It forms the lens through which we view and engage with everything around us.

I'll give an example. In my late teens, just as I was beginning university, I was sexually assaulted by someone I knew. Considering how we rarely discuss sexuality in Indonesia due to cultural reasons, I didn’t have much knowledge about the topic of sex. I was fully covered from head to toe as usual, including a headscarf. But it still didn't keep me safe. That experience left me in a state of shock and disbelief, so much so that I couldn't even label it as 'rape' at the time. I experienced a pain I'd never known before. Not knowing what to do, coupled with my religious beliefs, made me feel as if I'd lost a part of myself, leading to a deep sense of worthlessness. I think this mindset played a part in my later experience with domestic violence, as from that moment I doubted if I will be worthy enough to deserve love.

I will not blame the religion because I know that at the core, I've always believed that every religion teaches love and kindness. However, people can sometimes lose sight of that.

CLARINTA: I'm truly sorry to hear about your experience. I completely resonate with what you said about religion – every religious and spiritual teaching essentially teaches us to be kind and good. I grew up with a different religion, but just like you, I barely knew anything about sex growing up. It was a taboo topic; a sinful act. As a result, I also felt my 'worthiness' as a human being was simply reduced to my sexual purity or impurity.

RATU: You know, a mentor once told me that humans possess a unique superpower: the ability to take away another person's power. We often do this through tactics like shaming and guilt-tripping. Such actions make individuals feel small over things that are inherently human. At the same time, our inherent desire as humans is to belong. Many of us strive to fit into what's expected of us by our families and communities. Especially for a child — like any plant — we will twist and distort ourselves into uncomfortable positions just to gain light and survive.

CLARINTA: Earlier, you eluded to the existence of some abuse in your upbringing. Were your parents physically violent too?

RATU: Sure. In many parts of Asia, it's almost seen as normal for parents to beat their kids, isn't it? Especially when they're not in control of their emotions, or emotionally dysregulated. We just accepted it as part of life.

CLARINTA: Yes, unfortunately I know exactly what you mean.

RATU: The sad part is, the way they treated us gets ingrained in us. We start seeing it as a reflection of our worth.

CLARINTA: Yes, as children, we couldn’t comprehend that it was our parents struggling with their emotions. Instead, we internalized it, thinking we must be the problem, and that we deserve such treatment.

RATU: Exactly. It's a vicious cycle.

Entering The Relationship

CLARINTA: How did you meet your former partner, and what drew you to him initially?

RATU: My sister's best friend introduced us. In our conservative family, dating wasn't casual; if you were seeing someone, marriage was always the end goal. Just like my mom, I only had a few meetings with him. Our families got acquainted, and before we knew it, we'd set a wedding date. What attracted me was his intellect. I've always been a bit of a bookworm, so our deep conversations really resonated with me. And he was very affectionate. At one point, during a lockdown, he even flew to Dubai, where I was working as a marketing manager, just to see me. I thought, "This person must genuinely love me." And my mother loved him. On paper, he ticked all the boxes: an Ivy League education, a top-tier job in a Big 4 consulting firm in Australia, and importantly for my family, he was Muslim. And also, given my dad's recent death at the time and his hope of seeing me married with someone of the same religion, I felt he'd have approved.

CLARINTA: Were there early signs of red flags in the relationship?

RATU: In hindsight, yes. Many. But I overlooked them, not trusting my gut. The most glaring incident was about two weeks before our wedding. I was at my office in Dubai, deep in a work chat with a male colleague. Out of nowhere, he storms in, furious about missed calls. My phone was always on silent during work, so of course I had missed them. His anger and the accusations, right there in front of my colleague, were shocking. He even snatched my phone, trying to "prove" I was cheating. Even though I knew his claims were untrue, I couldn't help but question myself and was frightened by his rage. I later called my mom, telling her I was considering postponing or even cancelling our wedding. But my mom blamed me, saying 'This is your fault. If you're about to get married, you shouldn't be talking to other men.'

CLARINTA: Oh no. That's heartbreaking.

RATU: It's crazy, isn't it? Though, I can't blame my mom; she did what she thought was right. But here I was, an MBA scholarship recipient, yet I couldn't see the situation for what it was. Instead, I blamed myself for causing his jealousy and even told him I'd distance myself from other men. He said he reacted that way because he loved me, and I just... believed him. The next day, I even quit my job because he asked me to. Everything happened in a blur.

CLARINTA: How did your family and friends perceive your relationship with him at this time?

RATU: My family, particularly my mom, was pleased with him. In their eyes, I was already behind schedule at 30 for getting married. But my friends were pretty shocked. They couldn't grasp the idea of marrying someone after just a few meetings. And that's the thing — when you listen to stories from survivors, it's crucial to recognize that their choices are often shaped by their cultural backdrop, traditions, religious beliefs, and their place in society. Sadly, not all of us have the luxury of absolute freedom, and for some, their cultural norms can feel like a cage that's difficult to escape from.

Experiencing Abuse

CLARINTA: How and when did the abusive behaviour begin?

RATU: It began even before the wedding, but there's this concept in domestic violence called the "cycle of abuse." The pattern is, as the abuse intensifies over time, there are also moments of love-bombing and apologies. It was like an emotional roller coaster. I felt like I was constantly walking on eggshells, never knowing how my day would unfold. Some days he'd treat me like I was a queen, and the next, I'd be trembling under my blanket, praying he wouldn't come at me with a knife during one of his violent outbursts. He'd often tell me he'd kill me, and he knew I had nowhere else to turn. Even my own mother would send me back to him.

If we were out and other men glanced at me, his jealousy would spiral. Once home, he'd accuse me of seeking attention. He'd inspect my phone and force me to block contacts on a whim. Small issues would blow up into huge issues. Shouting and yelling was the norm. I often had nightmares of him trying to kill me. He'd wake me up, saying I'd been shouting fearfully in my sleep. I could never confess those nightmares were about him; I was afraid it'd only make him more angry.

The whole situation became even more suffocating when Australia went into full lockdown due to Covid. We were both working from home, and it was like living out a horror film, trapped and terrorized in my own space.

CLARINTA: Wow, hearing you talk about the cycle of abuse, it really resonates. As I mentioned before this conversation, I went through something similar when I was much younger and spent time in therapy unpacking it. My relationship at that time lasted about a year and a half.

For myself, being young, I didn't even realize that what I was experiencing was 'abuse'. I thought, "He's my boyfriend, he can't be abusive." And just like your experience, after he hurt me, he'd apologize like he meant it. He was perpetually angry, and constantly putting me down verbally. I also endured over a year of almost daily physical violence. It was also over minor things - if I talked to other guys, being slightly late to meet him, not replying to his messages quickly enough, or standing up for myself. Being so naive, I couldn't even recognize that what I was enduring was 'abuse'. But then he'd have these moments where he'd genuinely seem remorseful and apologize. Every time I thought, "Maybe he truly regrets it this time," and I'd forgive him. He'd be extra sweet and caring after, earning my trust again. That's when the self-blame kicked in. I'd think, "Maybe it was my fault. Maybe I deserved it." Now, as an adult, it feels so twisted. When someone asks, "Why didn't you just leave?" I wish they knew it's never that straightforward. There's always that hope they might change. And mixed in is the feeling that maybe you don’t really deserve any better.

RATU: Our stories seem to echo each other in many ways. When I started learning about domestic or partner violence, I came across the term DARVO. That acronym stands for Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender. Based on what you're sharing, I'm guessing you might've encountered this too. When confronted, abusers often play the victim card and twist things around to paint us as the villains.

I think growing up in a home filled with violence also made me see my experiences as just regular marital conflict. But in reality, it was all about dominance and manipulation. And it wasn't just the physical – there was emotional and financial abuse as well. There's this concept called the 'circle of power and control' (see below). It encompasses emotional, physical, sexual, and economic abuse. In abusive relationships, it's rare for it to remain just one kind of abuse. The longer it's tolerated, the more it branches out.

CLARINTA: How did the abuse affect your mental health, self-worth, and daily life?

RATU: It really wore me down. Even though I kept hoping things would get better, it felt like the abuse was chipping away at my sanity. I changed so much, always tiptoeing around him, trying not to make him angry. Even at work, I was nervous about interacting with male colleagues. I'd quickly delete any messages from male friends, and he pushed me to block my friends on social media. If any man so much as glanced my way, he'd accuse me of flirting. So I just stopped bothering about my appearance, and dressed down to avoid his outbursts. My confidence took a nosedive, and I felt like I was losing my sense of self.

Honestly, I felt trapped and broken. Every day was filled with fear and isolation. At my lowest, I believed there were only two ways out — if he killed me, or if I killed myself.

CLARINTA: Were there cultural or societal pressures that made it more challenging to speak out or seek help?

RATU: Yes, of course. The cultural aspect that we discussed before closed me off from understanding what rights I actually deserved. In Indonesian culture, unfortunately we normalised violence within a family and within a marriage.

CLARINTA: It's sad but true. In our culture, some are so used to this behavior that they might even ask, "What did you do to provoke him?" Which is a damaging and victim-blaming mentality.

RATU: You know, I couldn't even see that I was being abused. My best friend pointed it out once, and I instantly defended him, saying, "No, he just really loves me." Her response stuck with me: "That sounds exactly like what a victim would say." It took some time, but being in Australia, where there’s strong recognition of domestic abuse, really opened my eyes. I came to understand that nobody should ever be treated like that.

The Turning Point & The Aftermath

CLARINTA: What was the turning point that made you decide to leave the relationship?

RATU: One day, his rage erupted again. After he threatened to kill me, I became so terrified that I ran out of the house. Ironically, it was a work day, and I had an important meeting. I grabbed my laptop and, finding a public library with WiFi, I logged into my work call. I'd been crying so much that my eyes were completely puffy. I recall being on that video call with my manager, tears still in my eyes, telling her I might need to resign to save my marriage. But here's the thing: my manager, being Australian and having a background in social work, could immediately sense something was wrong. She probed, asking me question after question. I answered her honestly. And by the end, she said, "I believe you're a victim of domestic violence. Please don’t go back home. Here's the number for the domestic abuse hotline."

That night, I reached out to a friend and stayed on her sofa. I also rang the Domestic Abuse hotline. The voice on the other end asked me many questions, most of which I answered yes to. And then they told me, "You are a victim of domestic violence. Please don't return home. We'll assist with a shelter and contact the police for you."

CLARINTA: That's incredible. I'm so glad your manager sensed something wasn't right and asked you those questions.

RATU: It's important for people to know - for survivors, sometimes it's not about the words they say. Traumatized people often withhold the truth, because we are living in fear, unsure of who to trust. My manager and my best friend in this case, saved my life.

CLARINTA: Can you describe the process of seeking help and eventually moving to a domestic abuse shelter? How was your experience living in the shelter?

RATU: It was a rollercoaster. I was moved between multiple crisis shelters. These places are designed for survivor protection, so our connection to the outside world was minimal. You know the Netflix series, 'Maid'? It was eerily similar – no internet to prevent abusers from tracking us down. The shelter was modest, with a few rooms, and I had a bed in one of them. The cold was what I remember. The winter chill seeped through everything - the air, the water, even the walls of the shelter.

CLARINTA: I find it really interesting you mention about the cold, because I thought you would mention how you were finally safe from your ex-husband.

RATU: It’s interesting you mention that. Have you come across Lacan’s Borromean Knot theory? It explains how we perceive and understand our own realities. Basically, it's structured into three areas: Imaginary, Symbolic, and Real. The Imaginary is our immediate lived experience — how the world presents itself to us. The Symbolic captures the societal rules and norms we've followed all our lives, shaping our perceptions. The Real, often overlooked because we're engrossed in the first two, is those indescribable experiences — like traumas — that completely shake up our understanding of the world.

In other words, we humans think more in terms of symbols rather than the actual reality. Like, when you think of a home, you picture warmth, comfort, safety, right? Even during the times I was abused, I'd take a bath at home and let hot water run over me just to numb the pain, to make myself believe that I was safe even though I wasn’t.

Now, the shelter was a safe place. I was away from my abuser. But in my mind, the idea of a shelter was more about escaping, not about warmth. Even though I was safe, the shelter was cold and I felt incredibly lonely. I was surrounded by other survivors, each one grappling with their own trauma. I vividly remember my first time in the shared kitchen. I met a woman with half of her face brutally swollen and bruised. Even though I'm obviously a non-threatening person, she looked so terrified and instinctively flinched as I approached. It was really jarring to realise that another victim was so traumatised that even my presence made her recoil.

At that time, I also struggled with my mental health. After what happened, I was diagnosed with CPTSD - I had constant flashbacks & nightmares. At the same time, I had to go back and forth to the police & the court, to deal with legal paperwork to keep my immigration status — my ex-husband was Australian — and juggling my work at the same time. At the shelter, my social worker educated me about my rights and options. They also assisted me in going to the police to file an AVO, which is a restraining order against my husband. They also helped me in getting basic needs like clothes and food, because when I fled home, I didn't bring any of my things.

CLARINTA: Did your mom know you had moved to a shelter at this point?

RATU: That's where generational trauma truly takes its toll. When I called and told her about the situation, she felt I should either return to him and resolve our issues or find another man to marry. In our culture, being a widow—or even a victim of abuse—is a shame. In her eyes, I had brought dishonour and shame to our family. Instead of trying to hear my story, she cut ties with me for two years. She blocked me everywhere—on social media, WhatsApp, everywhere.

CLARINTA: That's terrible, I'm so sorry to hear that.

RATU: It's hard to blame her entirely. I believe she endured similar treatment herself. She simply didn't know better. And unlike me, she didn't have as many options or the education to find alternatives for herself. Maybe she thought, "If I endured this, you should too."

I've come to accept that she couldn't be the protective mother I needed. And fortunately, I've found a chosen family here—my manager, my best friend. They're my family now.

CLARINTA: After leaving the shelter, how did the relocation to an independent apartment come about? How has living independently in your own space been?

RATU: I think the challenges of managing work while at the shelter motivated me to quickly seek a stable place. I really felt how crucial it was to be financially stable and independent. Work was my only lifeline at that point, something I needed to cling to if I hoped to rebuild my life. I had only $30 in my bank account then and couldn't touch our joint savings.

The move itself was an emotional whirlwind — feelings of grief, abandonment, longing, and fear mixed with gratitude for another shot at life and a new sense of freedom. Living in my own space has been so important in my recovery process. It's a place where I can feel safe, and take the time to heal.

Therapy, Healing and Self Rediscovery

CLARINTA: What kind of after-effects & challenges do you still have to deal with on a day to day basis as a result of the abusive relationship?

RATU: The after-effects of domestic violence is so deep and pervasive. If I had to categorize them, I'd say there are external and internal challenges. On the outside, it's impacted every facet of my life - my family relationship, friendships, social network, living situation, financial standing, and professional life. My own mother, as I mentioned before, turned against me. Several friendships dissolved too. It's not necessarily their failing; many simply aren't equipped to understand or help me in the aftermath. The weight of discussing domestic violence created an awkward tension for many of them. While it's painful to see my circle diminish, it also affirmed who my core support circle of people are.

Financial stability, a challenge many other survivors struggle with, also became a main concern for me. I consider myself fortunate to have regained stability through my job, but many women, particularly those with children or student debts, aren't so lucky. That's why it's my firm belief that every woman needs to have a job, however small or modest. It's not just about money, but the autonomy and security it offers, which prevents us from being trapped in abusive relationships. Financial abuse is also an often-overlooked component of domestic abuse, which undermines our autonomy and self-worth.

At my lowest point, I was declining casual simple treats I used to be able to afford without thinking, like ice creams or an after-work drink with colleagues. Still, I’m grateful for the financial support I also received from the Australian government. It’s important for taxpayers to know how their contributions uplift survivors.

CLARINTA: What about the internal struggles you mentioned?

RATU: I've mentioned this earlier, but I was diagnosed with PTSD. The effects have been relentless. I'm haunted by nightmares every night, waking up at 1 AM as if on schedule. I tried using the Calm app to ease myself back to sleep, and while it helps at times, there are instances when sleep eludes me completely. After tossing and turning for a few hours, I usually resign to it and start my sunrise walks. It's a bit ironic—people like Elon Musk advocate early morning walks as a productivity booster, but for me, it's my nightmares that drive this ritual.

There are also many triggers, spread everywhere like landmines. Just recently, an internet technician's visit to my apartment spiraled into a nightmare where my ex violently confronts me about allowing another man inside our home. Or the panic attacks I have whenever my train stops at the station near our former shared home. Some workplace interactions, especially with male colleagues, have become anxiety-inducing. The unpredictability of PTSD triggers means I am stripped of my sense of normalcy.

CLARINTA: After your experience, how important was it for you to seek professional therapy or counseling? How did these sessions impact your recovery?

RATU: At first, I didn’t even realize therapy was something I needed. My initial aim was simple: to be fully functioning at work. Oddly enough, the motivation to seek therapy wasn’t really for myself, but to perform well at my job. Maybe that’s my people-pleaser side showing up again. So, with that focus on work, I found government-offered therapy sessions for survivors. That's when my healing journey started and, in many ways, my awakening.

That first session was a revelation. Pouring out my life's story to the therapist, it was as if a hundred light switches turned on. It explained why I felt perpetually damaged, why love seemed out of reach, and why there was this persistent feeling of emptiness. Turns out, much of that stemmed from what I endured growing up. The childhood abuse, constantly witnessing violence, the sexual assault, the years of feeling trapped, and then the domestic abuse in my marriage – all were rooted in this profound sense of unworthiness.

I spent most of the first month's sessions in tears. I connected with not only my pain but also the pain of countless women, including those of my ancestors, who suffered in silence. It was very humbling in an unexpected way.

CLARINTA: I complete understand how this feels. Therapy for me also unlocked the realisation that my entire life was a series of connected events, leading me to my present state of being. It was an equally humbling experience for me, and led me to feel compassion for both my past self and for others in my life. For me, I’ve since gone through EMDR, schema & exposure in the last 2 years. Also, understanding that traumatic experiences changes our brain structure has helped me massively in accepting that although my mind might have moved on, my nervous system has not. Were there specific types of therapies or approaches that you found particularly helpful?

RATU: I've done various forms of therapy like CBT, somatic therapy, grounding techniques, and I've integrated practices like meditation and yoga into my recovery process. Being part of a support group with fellow domestic violence survivors has also been cathartic. But the fundamental part of my healing journey has been rebuilding my self-worth. It's devastating to realize that many survivors, including myself, internalize the wrongs that was done to us. We need to stop feeling ashamed for the abuse we endured. Therapists help dismantle this belief, placing responsibility where it truly lies. This is critical for healing. It allows survivors to move forward, not just for their own sake, but to uplift others who've experienced similar traumas. Your conversation with me now, holding this space—it's part of that healing cycle, and I try to provide the same for others.

I would say at the end of the day, though, healing and recovery is about consistency and to keep practicing it. No matter the therapy methods or books we read, it comes back to our commitment to work on ourselves and embody it in our daily lives. When we are faithful to a practice or ritual, it will be faithful back to us.

CLARINTA: That's so eloquently put. I've also started attending a group therapy session weekly over the past five months. The group is diverse — some healing from past sexual assault, another dealing with the trauma of a suicidal parent, and many confronting the scars of childhood emotional neglect. While the group sessions can be intensely heavy, those 90 minutes where we sit with another’s pain, have become the most moving and most impactful part of my week. What else have you found helped you?

RATU: Maintaining a healthy support circle is essential for a survivor. During those heightened moments of vulnerability, even the smallest things can set off distressing triggers. I also strongly believe in the value of ongoing therapy. Sometimes, just when we think we've made progress and are ‘healed’, life throws us a curveball and presents a new challenge or trigger. I've often wondered if there's a scientific explanation behind this. Haven't you felt that way too? We overcome one hurdle, feel empowered, only to be taken aback by something even more overwhelming.

So it’s essential to have professionals - whether a therapist, coach, or social worker - and a supportive community by our side. It's unrealistic to expect our loved ones to shoulder everything, particularly if they were, unfortunately, a source of our trauma. We must take the initiative to find our "tribe", those who constantly remind us to treat ourselves with kindness and love. Personally, I've also found healing in art. Whether it's through poetry, painting, music, photography, or theatrical performances, art has become an outlet for me. It reminds me that we are all humans with our struggles, just trying to make it through another day.

CLARINTA: What would you like to say to others who might be in a similar situation or those who suspect someone they know might be facing domestic abuse?

RATU: I'd start by saying I am truly sorry that this has happened to you. Please know that I see you, believe you, and feel your pain. This isn't your fault, even if it sometimes feels that way. Abuse and violence were choices the perpetrator made, and it's a tragedy when such actions come from someone you deeply love and trust. But remember, you don't have to endure it. Your mental and physical well-being should always be your primary concern. Understand that you're deserving of love, respect, and security, just like everyone else. Reaching out for help is not a sign of defeat; it's a testament to your resilience and refusal to give up living. Standing up for yourself and breaking free from this cycle, particularly if it's rooted in generational trauma, may mean losing family members and stepping out of your comfort zone. Many who you believed had your back might misunderstand or judge you, but remember, those resistant to your growth were never in it for love; it was about power and control. Let them go.

This might be a metamorphic phase for you, but it's also a journey towards rediscovering yourself. You'll come to know who you truly are, beyond labels and societal expectations. You'll surround yourself with those who genuinely care, seeing and cherishing you for the person you are. Trust me, many empathetic souls are out there, waiting to support you. And while the path to recovery might be challenging, it promises to be one of the most transformative experiences of your life.

CLARINTA: Beautifully said, I experienced this transformative phase myself as well. In your opinion, how can communities and individuals better support survivors of domestic or partner violence?

RATU: The key is education and awareness. Recognize that domestic/partner violence follows a familiar pattern, and is preventable if you notice the signs. Listen actively to the stories of survivors and understand their insights. When survivors decide to share their truths, receive them with compassion and understanding. Their stories have the potential to save future generations, and to provide immediate support to those currently suffering in silence.

CLARINTA: Building on that, I think it's also about challenging and reshaping deeply ingrained narratives. For so long, many of us have been conditioned to believe that we should prioritize sacrifice and endure suffering — mentally, physically — because it's culturally expected. And it's not just partners; even children are often taught to accept violence from parents under the guise of discipline or 'tough love.' But when someone, with the same socioeconomic and cultural background, steps up and declares, "No, your well-being also matters, just as much. You deserve better", it disrupts that old narrative. Presenting this alternative viewpoint at least offers the chance for that person to reconsider deeply held societal conditioning and provides them an opportunity to think differently.

RATU: Exactly. Representation matters. Unless we witness others breaking free from abusive relationships, and standing on their own two feet again, it can be hard to imagine that path for ourselves. I remember connecting with you because you openly talked about your journey with CPTSD. Your explorations into meditation deeply resonated with me and even influenced some steps in my own healing process. I think sharing, in its purest and most authentic form, is transformative. By being open about our experiences, we not only support our own growth but potentially light the way for others.

Future Aspirations

CLARINTA: Now that you're building a new chapter in your life, what are your hopes and aspirations for the future?

RATU: My vision is for a world that is just and equal, where we all, men and women, come together in mutual respect to contribute to the greater good of humanity. After all, we are called 'homo sapiens' for a reason – we're meant to be wise beings. We might never fully achieve this vision, but by recognizing that men and women are fundamentally equal as human beings, we can change the dynamics of our relationships and interactions.

Also, I want to witness a world where women stand empowered. The current struggles and generational trauma many of us face trace back to age-old systems of patriarchy. We need to actively question and reframe our traditional gender roles. Women have a reservoir of resilience and strength that is often overlooked. To truly progress, we must shift from a mindset of competition and judgment to one of collective empowerment. Every triumph for one woman should be celebrated as a collective victory.

CLARINTA: As we wrap up our conversation, do you have any parting words or insights you'd like to share with the reader?

RATU: I would like to quote an author I deeply admire, Yung Pueblo: “Our greatest asset in transforming the world and uplifting human dignity is healing ourselves so deeply that we become unwilling to harm others directly or indirectly.” This, to me, encapsulates our conversation today.

CLARINTA: Thank you for letting me hold space for your story.

___

Resources

Below are important Domestic/Partner Violence resources from Ratu:

AUSTRALIA:

In Australia, the resources are more comprehensive, and there's a significant effort to ensure those affected by domestic violence get the support they need:

- Emergency Assistance: Dial 000 for Police and Ambulance if in immediate danger.

- Counseling and Support: 1800RESPECT - A 24/7 national counselling and support service for those impacted by domestic, family, or sexual violence. Chat online.

- Trauma Counseling: Full Stop - Offers trauma counselling & recovery services for individuals facing or having faced DV. Call 1800 385 578.

- Legal Service: Women’s Legal Services - Free, confidential legal advice centered on family law, DV, and sexual assault. Reach them at: 1800 801 501.

- Community Support: Women & Girls Emergency Center (@WAGEC) - Provides crisis support, mentoring, and more, including training, campaigns, and advocacy efforts. Ratu is also currently a mentor here.

INDONESIA:

For Indonesia, unfortunately, the support and awareness is still minimal. However, here are some numbers & organisation you can reach out to:

- Domestic Violence Reporting: SAPA - To report DV: Call 129 or WhatsApp 08111129129.

- Legal Assistance: LBH Apik WhatsApp – Reachable at 0813 8882 2669 (9:00-21:00 WIB).

- Hotlines: P2TP2A DKI Jakarta Hotline – Dial 112. Pelayanan Sosial Anak (TePSA) – Call 1 500 771.

- Women's Commission: Komnas Perempuan - For assistance, dial 021 390 3922 or email at petugaspengaduan@komnasperempuan.go.id.

- Psychological Counselling: Indonesian Psychological Healthcare Center (IndoPsyCare). You can also read a previous interview with a clinical psychologist on my journal here.

You can also reach out to us with your own stories through our social media at @clarinta & @ratunida.

___

Further Reading & Research:

- People who were abused as children are more likely to be abused as an adult (UK Office for National Statistics, 2021)

- Intimate partner violence and traumatic brain injury: An invisible public health epidemic (Harvard Medical School, 2022)

- Risk and Protective Factors for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Perpetration (CDC.gov, 2020)

- Psychotherapy leads in treating post-traumatic stress disorder (Harvard Medical School, 2019)

- ‘One Foot in the Present, One Foot in the Past:’ Understanding E.M.D.R. (The New York Times, 2022)